The end came abruptly; systematic and unapologetic, as can be expected from such a momentous and prolonged experience. For a while I stared in silence at the field in front of me, taking in the open, unrestricted ice kingdom; committing to memory its vastness and the contours of the mounds and ridges framing it; noting the way the sun defined the terrain; feeling the wind biting my left side; and for once relishing the chill that sneaked past the steam out of my base layer. I heard my heart pounding, fresh from the effort, tugging at me with undecided trepidation, not sure whether to weep in relief or beg for more. Any moment now, this solemn and suspended reality would be broken by the distant flapping of the helicopter’s rotors. And the dream would end.

Last night in the tent was to be our last. We gathered all the food we had left, including our emergency bag, combined it, and fed ourselves a copious dinner. We slept short and cooked our final breakfast of warm granola with goat milk powder, dried fruits and nuts. We even found an emergency protein mix! Cramped in the tent as we have been everyday for the last thirty five getting dressed, I noted one more time how a program based on tent activities would make for a great core workout! (Note to Yumi and Ron–my trainers!) This was going to be a long day, and for the first time in weeks, thanks to the emergency food bags, we both had extra bars for the road. Six each, in total. A real feast! The day was sunny with a ten knot breeze out of the north west; it would hit us in the face from the left. But the terrain was well defined, and the flat pan we had ended on yesterday stretched in front of us for another long haul. That pan was unreal: it must have gone for over fifteen miles! We’ve not seen anything like that for the entire trip. In fact, it has been shocking how little multi-year pans we saw; mostly one to two year old sections, which tend to be a lot more jagged and fractured. And a lot of one year old, messy rubble zones—as we know!

We broke up camp for the lat time, packed our sledges and shot out of the gate. The combination of extra food, and our last chance to reduce the miles separating us from the pole gave our legs new springs, and put jetpacks on our backs. Except for two slightly messy and powdery bits, we had open terrain all day and traveled at an average of 1.4 miles per hour–twenty percent over our daily average! (As well today, ironically, the drift finally slowed down!) Victor had asked me to call him with our position at eight thirty AM, Longyearbyen time (this close to the pole, you can basically chose the time zone you wish to align yourself with—it makes no difference.) We would call from the trail. He would then take off from Barneo shortly after nine, and planned to pick us up between 10 and 10:30 AM (Barneo, the temporary floating station, is on the east side of the pole, drifting around N88°17.066′ and E 3°34.270′). This gave us a solid twelve hours, uninterrupted. With nothing but open space in front of me, I motored and skied hard. My legs got sucked into the rhythm, and never complained. Nor did Keith, though I knew his hip bothered him. But the day was set to put a mark on our vanishing legacy. Each hour that passed was punctuated by the pleasing speed that would define our last travel day, and the looming and steady creep of a countdown that brought a mix of relief and sadness. The last few days have been the toughest, but today, in spite of the wind’s chill, we are eating miles and feel unstoppable. Besides, we have fuel, and those bars make all the difference. Still, I find my mind wandering seamlessly from the chanting meditation to food fantasies!

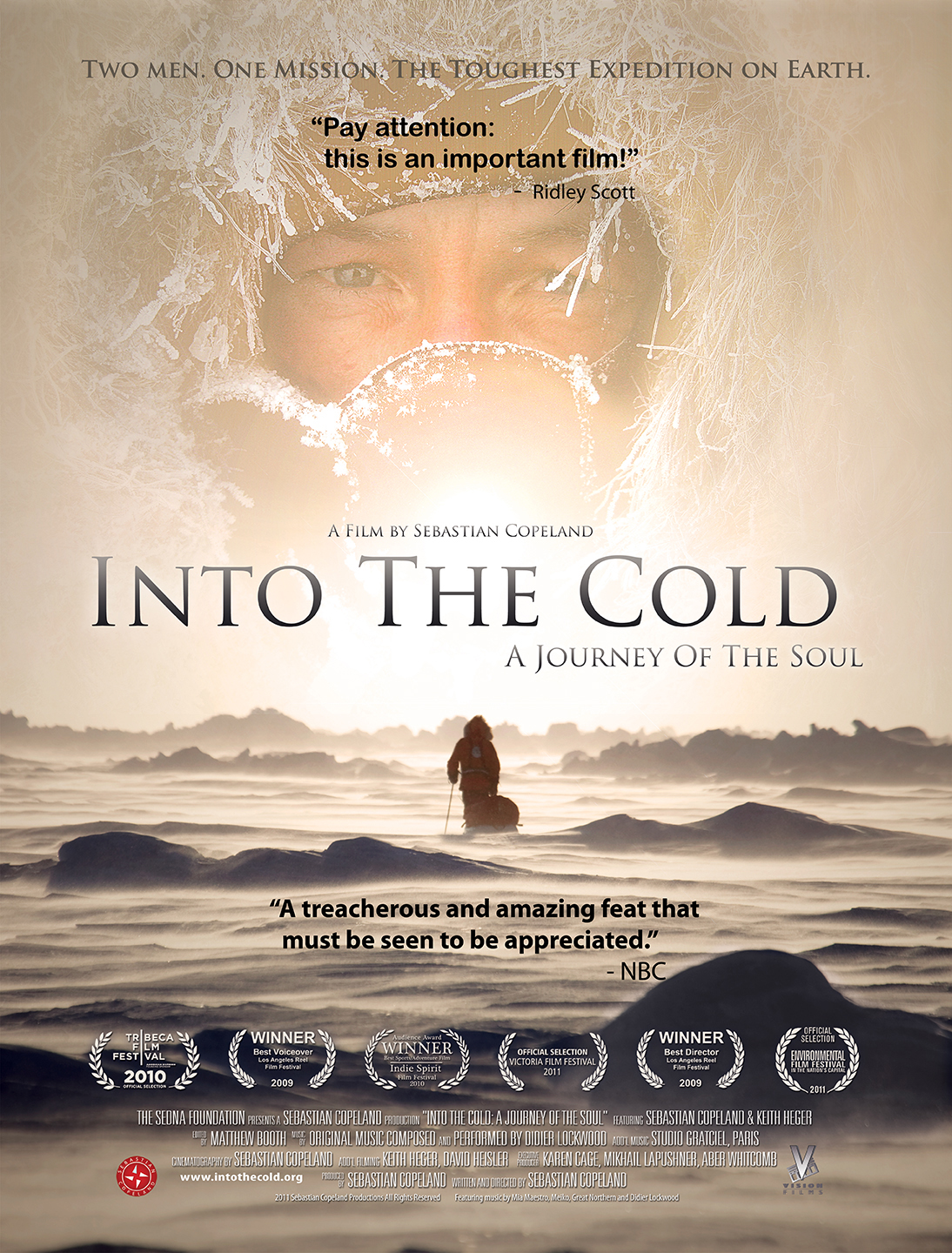

By 8:30 we had covered 17 nautical miles. I communicated that to Victor over our brief conversation, and told him that I would stay on the same longitudinal line, but push north until he showed. As if to teach us one more time the meaning of the word respect, the pack ice threw a field of junky, powdery blocks at us, and the clouds overtook the sun to flatten out detail in the terrain. I was anxiously pushing forward, intent in reaching our farthest north. Then it all cleared: the sky, the wind, the rubble. Ahead laid a flat pan framed by pressure ridges on either side. I raced to it; and stopped. It would make for a good landing area, and was open enough to clear our minds. I scanned the landscape, and leaned on my poles. Beneath the frosty facemask and under my icy ruffed hood, the breath I took filled my heart with the essence of purpose, and a mission accomplished. And I smiled. As Keith and I stood there in the silence that had come to characterized our solitary travel, I knew that this image would define my experience up here. And I relished it. The North Pole is so ephemeral; so fleeting that it can feel like an illusion. While the Pole itself is a static geographical point at the bottom of the ocean, up here, on a sea ice constantly drifting, nothing is. In fact sometimes, as happened to me then, the dream feels more real. And as the ice shifts, unmoved by the human desire to pierce its crust with a marquee post, what is left is the image that we chose to retain. And to me, it will be that open field staring me in the eye, as if to say: “I’m leaving too. Soon.”

In the distance, the wind carried the unmistakable flapping of the MI8’s rotors. Invisible at first, the heavy craft appeared south of us, first a dot growing to dominate its surroundings by its alien form, and loud engine.

Keith an I unhooked our sledges, as the bird lowered its frame in a white dust storm near us. The door opened and Victor jumped out, hugging us both. Nancy was on board, too, with a box of cookies (gone in a nanosecond!) The sledges were hauled inside the chopper, and we floated above the ice to reach the pole a few miles north of us. Below, the leads, rubble and pressure ridges had lost their power. The machine had neutralized them, and the match was no longer fair. But so it goes…

In no time we were dropped on the ice. A quarter of a mile from us laid the North Pole. Symbolically, we pulled our sledges off the craft, got in to our harnesses and skis, and marched to it. A point that does not give itself up easily–the drift makes for a fierce defender of the pole–one moment right, the next left, you think you are about to have it and then, no: you’re headed the wrong way! I walked in circles with my GPS for ten minutes until it read N89.59.996; then 997; then 998… 999… Finally, my unit read: North Pole N90.00.000! I shot it with my camera, locked it in the unit to record it. And in seconds, just like that, it was gone. That point from which any step heads south, the top of the world, where all longitudinal lines blend and all time zones meet, was mine for one brief, ethereal instant. And then no more.

But then you’ve heard the saying, haven’t you? “It’s the journey—not the destination…”

More