Antarctica

HISTORY

The Antarctica continent is the largest ice mass in the world. With an average elevation of 7500 feet, it is the highest, and coldest place on Earth. It is also the driest and windiest. 98% of its surface is covered with ice, yet some of its interior deserts have not seen any precipitation for over two million years.

Inhospitable to life though it is, Antarctica has conjured wonder and awe from the day humans set foot on the continent, in 1821.

Explorers have stared at its map ever since it was first assembled twenty years later, but it took ninety more years for its fabled marquee to be reached by two separate teams. On January 17, 1912 Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition arrived at the Pole hoping to plant the British flag at 90 degrees South. To his great chagrin, what he found was the Norwegian flag left by Roald Amundsen and his party merely a month prior, on December 14, 1911. Scott and his men would starve and freeze to death in a tent on their return journey a mere 11 miles form their food cache.

One hundred years later, the challenge faced by these men is as relevant and daunting as it was then. While advances in clothes design, technology and communication have given a decisive advantage to modern exploration, the harshness of the white continent still commands the upmost respect from seasoned polar travelers.

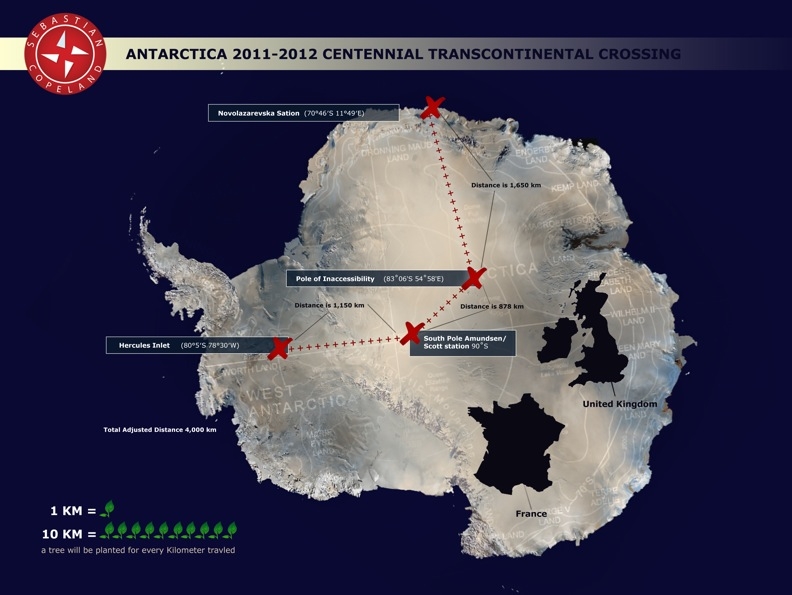

ANTARCTICA 2011-2012 LEGACY TRANSCONTINENTAL CROSSING

To commemorate Amundsen, Scott and their men, on November 2nd 2011, two men will set out to open a new route linking the east and west coast of Antarctica, via the South Pole over an estimated 85 to 90 days, without assistance. The Antarctica Legacy crossing will cover close to 4000 kilometers on skis and kites, passing through the Pole of Inaccessibility—the farthest point inland from any coast—and the South Pole, to end at Hercules Inlet, at the edge of the Ronne ice shelf. The men will link two points never traveled before, setting tracks in places where no man has ever been. On the science side, we will be making photographic observations of the ice surface for the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), to help determine ice accumulation in specific areas.

CHALLENGES

One of the greatest challenges of this expedition will undoubtedly be the weight we will be pulling. Because the trip is un-assisted—meaning we carry everything needed from the moment we set out until we are picked up—our loads will approach 400 pounds each. Scaling up the glacier from about sea level to an elevation of around 9000 feet is like pulling a house! Negotiating the crevasse fields in the early phase of the trip will present the first set of challenges. These crevasses can swallow a truck, and testing the thin ice bridges, while pulling the heavy loads is sure to be very slow. Additionally, the cold will be with us from the start, in spite of the low elevation, given that we set off during the austral spring, when temps are still frigid. As we gain in elevation, the Antarctica deep freeze will set the tone for the rest of the expedition with temperatures never warmer than minus 25C, and often around 40C below—without wind chill. The katabatic winds can easily lower those numbers by an additional 20C degree! This is warm compared to Antarctica’s winter temperatures, which have reached an Earth record of minus 89C degrees (- 128F)!

KATABATIC WINDS AND KITING

Nansen was the first to cross a major ice sheet with his East/West crossing of Greenland in 1888. Had today’s kiting technology been invented in Nansen’s time, I am convinced that dogs would not have figured as much in the history of Greenland and Antarctica’s expeditions—thanks to the katabatic winds.

In polar regions, the low angle of the sun prevents its rays from warming the surface. Instead, it warms the air above the surface, pushing cool air down. Cold air is much heavier than the relatively warmer air by the coast. In areas of frozen elevation, gravity pulls that heavy air down. Try and visualize the cloud of cold air that shoots down the opening door of a freezer. These winds gain speed as they shoot downhill, sometimes reaching speeds in excess of a hundred miles an hour.

High on the plateau, however, where no significant slope is to be had, the wind can be very light and often nonexistent. Because of these variations, we anticipate combining kite-skiing with walking (cross country skiing). Given the heavy load we will each be pulling, and the great distance we need to cover, we will be praying for Aiolos, the Greek god of the wind!

CLIMATE CHANGE

I have been lucky enough to travel to both the Arctic and the Antarctic. This has given me a chance to witness first hand changes taking place in these remote and frigid regions. Of the many things I have learned on those trips, the first is that it is generally really cold! This makes it that much harder to engage in a climate dialogue that involves the word “warming” when talking about the Poles.

But the poles are like great receptacles of what happens remotely: and warming activities conducted thousands of miles away are impacting these fragile systems. Small fluctuations in temperatures are generally visible fastest colder climates, where ice or snow is susceptible to melt.

From a climate perspective, in the North, the polar ice cap is receding at accelerated rates, threatening a complete melt of the sea ice in the summers to come, and an accelerated rate of pour of the Greenland ice sheet into the ocean. In the South, things are more complicated. Ozone depletion was the first alarm bell from the human footprint, traced to Chlorofluorocarbons(CFCs). Then came new atmospheric problems resulting from Poly-Aromatic-Hydrocarbons, or PAH’s which typically come from burning oil, coal or wood. But with over two miles of ice crushing the land below it, the interior temperatures of Antarctica have remained stable, sometimes even cooling, and increasing its ice cover. However, that is not the whole story. The Antarctic Peninsula, which extends towards South America, has seen its ice shelves retreat by an average of 300 square kilometers each year since 1980 due to warming trends along the coasts. Since the collapse of the 3,250 cubic kilometer Larsen B Ice Shelf in 2002, local glaciers have been moving 2-6 times faster, releasing more ice into the sea, contributing to ocean rise. And the increased accumulation in the interior is linked to precipitation due to the warming and evaporation along the coast.

Most things in Antarctica are more complicated than they appear. And while the changes there are less apparent than they are in the North, Antarctica remains a formidable player in the implications of climate change both from a geopolitical perspective as well as within its ecosystem.

IN CLOSING

While a very different mission than last year’s Greenland crossing, many lessons learned from that trip will be applied in Antarctica. Eric, my partner on Greenland, will team up again with me on this trip. I hope our expedition will be entertaining and educational at the same time, while encouraging a deeper connection with our host planet, and the urgent need for a global commitment to a sustainable future. I hope you will join us on this ride! Here we go again…!”

“Anything else you’re interested in is not going to happen if you can’t breathe the air and drink the water. Don’t sit this one out. Do something. You are by accident of fate alive at an absolutely critical moment in the history of our planet”

– Carl Sagan, Astrophysicist

Antarctica Map

Watch Video

Equipment and Food

A list of equipment and food used by Sebastian and Eric is available in .pdf format.

Click below to download.

Team

Sebastian Copeland

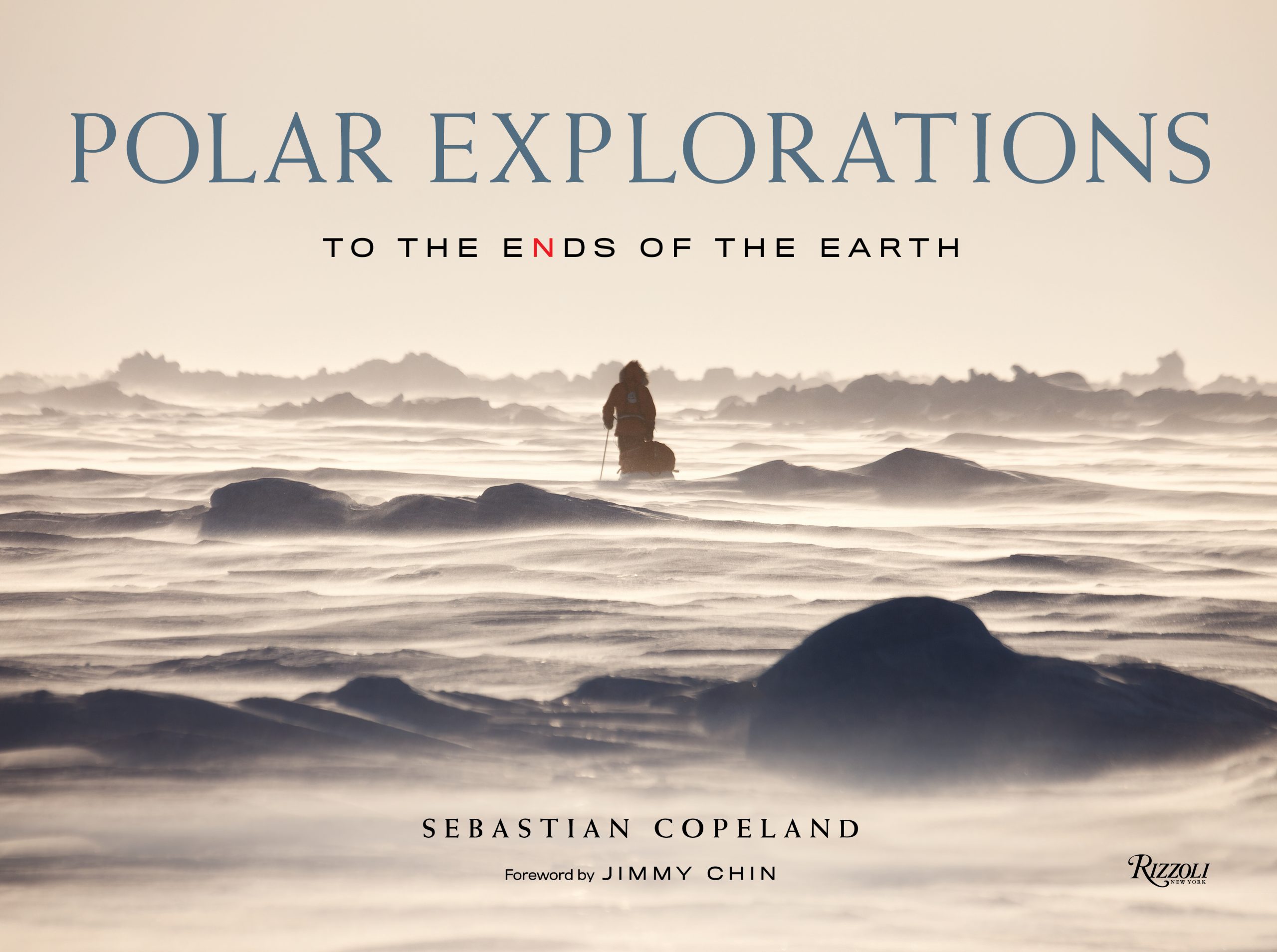

As an award-winning photographer, polar traveler, author and environmental advocate, Sebastian Copeland has made the fight for the protection of the environment his life’s work. His photographic study of Antarctica, assembled in the book Antarctica: The Global Warning, won him the IPA’s 2007 Photographer of the Year award. In 2009, Copeland traveled the Arctic with expedition partner Keith Heger on a journey to reach the North Pole in hopes of raising awareness on climate change and its effects on the Arctic region. The outcome of this voyage is the riveting documentary Into the Cold: A Journey of the Soul (2010). In 2010, Copeland and partner Eric McNair-Landry crossed 2300 kilometers of the Greenland ice sheet, and set a world record for the longest distance traveled in a twenty-four hour period on skis and kites, with 595 kilometers.

Eric McNair-Landry

Eric studied engineering at Acadia University, considering continuing in architecture. In 2004-5 he took off a year of school to join the family Kites on Ice Expedition and became the first American/Canadian to haul un-resupplied to the South Pole. Eric has crossed the Greenland ice cap in its 2300 km South-North axis and hold with partner Sebastian Copeland a world record for the longest distance traveled on kite and skis over a 24 hour period with 595 km. In 2011, Eric and his sister traveled the length of the Northwest passage in winter on skis and kites. Eric is passionate about kiting. When there is no wind, he spends his time in teaching himself computer graphics and website design.